Typing in Python (en)

11-02-2026

This article covers two key questions. Why use typing in Python, a language that lets you write without it? And how do you write typed Python code correctly? We will quickly go through the essential tools so that after reading, you can consciously start writing typed Python programs. It is not that hard.

# Dynamic vs Static

So what is typing? For many Python developers, this can feel new, because most classic languages such as C, Java, Rust, and many others were originally designed as statically typed languages. But what does that mean? Let’s look at a small C example:

int sum(int a, int b) {

return a + b;

}

int main() {

printf("%d\n", sum(10, 20));

// printf("%d\n", sum("10", 20));

}This code works and prints 30. But note that the last line is

commented out. If we uncomment it and compile again, we will get an

error log like this:

error: passing argument 1 of ‘sum’ makes integer from pointer without cast

10 | printf("%d\n", sum("10", 20));

| ^~~~

| |

| char *

note: expected ‘int’ but argument is of type ‘char *’The log says that the function parameter expected int but got

char * (for simplicity, think of it as a string). At first glance,

this may not look surprising for Python developers, because this Python

code would also fail:

def sum(a, b):

return a + b

print(sum("10", 20)) # TypeErrorSo what is the difference? Let’s tweak both examples in C and Python,

and call sum with two strings:

print(sum("10", "20")) # > 1020Here we get no error, because polymorphism works and string addition is valid. But what happens in C?

int main() {

printf("%d\n", sum("10", "20"));

}You cannot even compile this program. You get the same error log as

before. Notice how we defined sum in C: we explicitly set input

argument types to int. That means arguments of any other type cannot

be passed into this function. This is static typing. Static typing also

requires a type for each variable and prevents changing variable types

after declaration. In other words, the type is fixed.

The second group is dynamically typed languages: Python, Lua, JavaScript, and others. In those languages, the variable type is not strictly fixed and can change during execution.

# Benefits of Typing

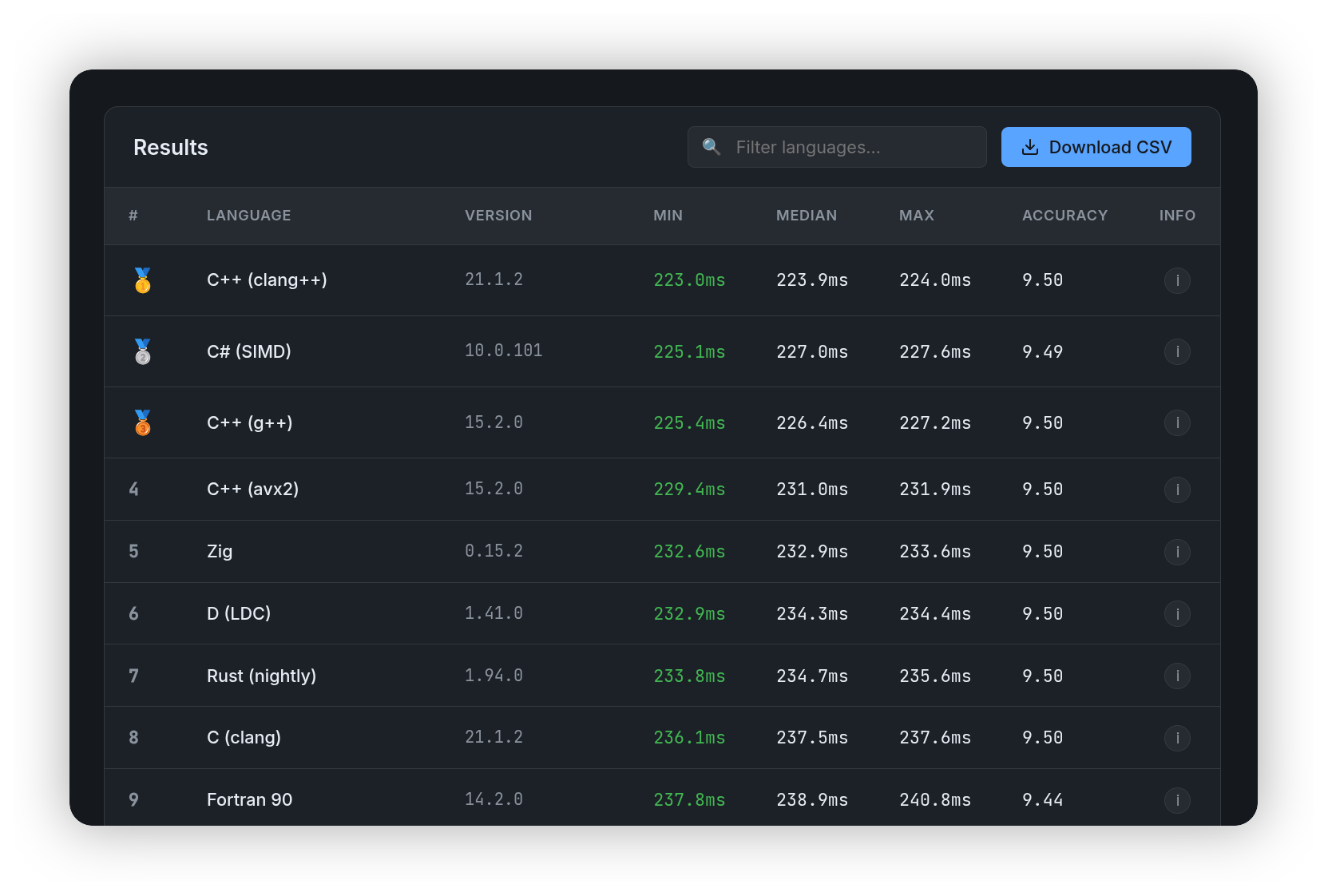

Now to the question: why do we need typing if Python already works well without it? First, speed. At a low level (whatever representation you use), types are always needed. If we do not write them explicitly, it only means someone else does that for us (for example, a virtual machine), which requires resources. That is reflected in language speed rankings:

In this rating, Python is at the bottom. Will typed Python fix that? Unfortunately, no. Python was not and still is not a statically typed language. Type annotations in Python remain optional. You can omit them, and the Python interpreter does not enforce them at runtime.

This brings us to the second benefit of types: code quality.

“The goal of typing in Python is to help development tools find errors in Python code bases through static analysis, without running code tests.”

Luciano Ramalho, “Fluent Python”

Extending this idea, typing goals are:

- Early error detection, before runtime and before production failures.

- “Test extraction”: correct typing can reduce the number of tests, which are often harder to write and maintain than types. Tests can then focus on business logic, not primitive mismatches.

- Better readability: PEP 20 says “Explicit is better than implicit.” When reading code, function signatures are often enough without diving into implementation.

- Better IDE workflow with more hints and warnings.

- Better architecture quality: types force cleaner abstractions.

# How to Write Typed Code

Before code, let’s separate three important concepts: interface, abstract class, and protocol. What is the difference?

- Interface is a class where all methods are abstract, with no implementation details.

- Abstract class is a class with both abstract and implemented methods.

- Protocol is an implicit interface.

The first two are straightforward. Let’s focus on the last one. In Python, an interface pattern is usually implemented through inheritance: a class implementing an interface inherits from that interface class. A class implementing a protocol does not have to inherit from it and may not even know about it.

## Primitives

Let’s finally look at how to write typed code. Start with a simple

function that repeats a string n times.

def multi_string(string, n):

return string * n

print(multi_string("cat", 3)) # > catcatcatThis function takes a string and a number and returns a string built by

concatenating the original string with itself n times. Now type it:

def multi_string(string: str, n: int) -> str:

return string * nSyntax is simple: input parameter types go after a colon, output type goes after an arrow. Your IDE can now highlight errors if inputs are wrong or if returned values are handled incorrectly.

You can annotate all common primitives this way:

str, int, bytes, float, Decimal, bool.

## Union Types

In real code there are more complex cases where a function should accept multiple types, but not arbitrary ones. In those cases use unions:

def normalize(data: str | bytes) -> str:

if isinstance(data, bytes):

return data.decode("utf-8")

return dataHere normalize accepts either a string or bytes and always returns a

UTF-8 string. With union (|), you can list multiple types, but you

should use this carefully. If you feel like writing a long union of ten

types, pause and reconsider. We will cover ways to handle such cases

below.

Unions are also valid for return types, but mostly for optional results. Example:

def parse_int(value: str) -> int | None:

if not value.isdigit():

return None

return int(value)This means the function result is optional. It may return int, or may

not return one if parsing fails. But annotating returns as int | str

or other unrelated combinations is usually bad practice. It becomes

unclear how to process the result. In practice, return either a concrete

type with known methods/attributes, or None. Breaking this rule tends

to complicate code.

## Collection Specification

Besides primitives, you can and should annotate collections. Avoid plain

data: list; specify element types too. Use square brackets:

def format_user(user: tuple[str, int]) -> str:

name, score = user

return f"{name}: {score} points"

def average(values: list[float]) -> float:

if len(values) == 0:

return 0

return sum(values) / len(values)

def total_count(counters: dict[str, int]) -> int:

return sum(counters.values())Of course, this does not cover all production scenarios. In TypedDict, NamedTuple, and Dataclass, we extend this toolkit.

## Mapping and MutableMapping

Mapping and MutableMapping are abstract base classes for dict-like

structures. Mapping guarantees read-only behavior (keys, values,

iteration), while MutableMapping says the object is mutable.

from collections.abc import Mapping, MutableMapping

def read_config(cfg: Mapping[str, str]) -> str:

return cfg["DATABASE_URL"]

def patch_config(cfg: MutableMapping[str, str]) -> None:

cfg["DEBUG"] = "1"If a function only reads data, use Mapping. If it mutates data, use

MutableMapping. This is a small but important signal for readers and

type checkers.

## NamedTuple

When you need a fixed set of fields while keeping tuple behavior,

NamedTuple is useful. It is immutable and indexable, but also lets you

access fields by name.

from typing import NamedTuple

class User(NamedTuple):

id: int

username: str

score: int

def print_user(user: User) -> str:

return f"{user.username} ({user.id}) = {user.score}"NamedTuple is good for compact data structures that should not change

after creation. If you need mutability and richer behavior, prefer

dataclass or a regular class.

## TypedDict

If your structure is a dictionary and you want typed keys and values,

use TypedDict. It describes dictionary shape and works at static

analysis level.

from typing import TypedDict

class User(TypedDict):

id: int

username: str

email: str | None

def send_email(user: User) -> None:

...This is especially useful when data comes from JSON or another dynamic source but you still want a strict key contract. If some keys are optional, define that explicitly to keep type checks meaningful.

## Dataclass

dataclass is a convenient way to define a data container with

initializer, comparisons, and readable repr. This class is mutable by

default and works well for domain objects and DTOs.

from dataclasses import dataclass

@dataclass

class User:

id: int

username: str

email: str | None = None

def normalize(user: User) -> User:

user.username = user.username.lower()

return userdataclass is a good fit when you need mutable structure and clear data

modeling. If an object must be immutable, use

@dataclass(frozen=True).

## Enum

Enum helps define a closed set of values. This is useful when a field

has a strict list of allowed options and you do not want random strings

in your code.

from enum import Enum

class Status(Enum):

NEW = "new"

DONE = "done"

FAILED = "failed"

def is_done(status: Status) -> bool:

return status is Status.DONEThis approach is practical for statuses, roles, flags, modes, and other enumerable domain values.

## Custom Classes

The type system can specify not only primitives but also your own or library classes. For example:

class User:

id: int

username: str

email: str

friends: list[User]

def hand_shake(user1: User, user2: User) -> None:

user1.friends.append(user2)

user2.friends.append(user1)## Abstract Classes

Python has an excellent module, collections.abc. It already defines a

large set of abstract classes that cover most practical needs. They are

useful when you want to describe behavior, not a concrete

implementation. What is available there?

collections.abc.ABCMeta

collections.abc.AsyncGenerator

collections.abc.AsyncIterable

collections.abc.AsyncIterator

collections.abc.Awaitable

collections.abc.Buffer

collections.abc.ByteString

collections.abc.Callable

collections.abc.Collection

collections.abc.Container

collections.abc.Coroutine

collections.abc.EllipsisType

collections.abc.FunctionType

collections.abc.Generator

collections.abc.GenericAlias

collections.abc.Hashable

collections.abc.ItemsView

collections.abc.Iterable

collections.abc.Iterator

collections.abc.KeysView

collections.abc.Mapping

collections.abc.MappingView

collections.abc.MutableMapping

collections.abc.MutableSequence

collections.abc.MutableSet

collections.abc.Reversible

collections.abc.Sequence

collections.abc.Set

collections.abc.Sized

collections.abc.ValuesViewAs you can see, there are many abstract classes. Most describe a property of a collection. Using them in annotations lets you express wider polymorphic input boundaries for your functions:

from collections.abc import Iterable

def total(values: Iterable[int]) -> int:

return sum(values)

total([1, 2, 3])

total((1, 2, 3))

total({1, 2, 3})Sometimes you still see imports from typing like

from typing import Iterable, Sequence. In practice, those are

re-exports from collections.abc. Today it is better to import these

ABCs directly from collections.abc.

## Sequence and Iterable

These two are often confused. Iterable only guarantees that an object

can be iterated in a loop. No indexing, length, or ordering is

promised. Sequence guarantees iteration plus indexing and length, that

is __getitem__ and __len__. This leads to a practical difference in

what operations are safe.

from collections.abc import Iterable, Sequence

def sum_any(values: Iterable[int]) -> int:

total = 0

for v in values:

total += v

return total

def head(values: Sequence[int]) -> int:

return values[0]sum_any accepts a list, tuple, or generator. head cannot accept a

generator, because it has no indexing and you cannot do values[0].

So, if you only need iteration, use Iterable; if you rely on indexing

or length, use Sequence.

## Callable

Callable is used when a function accepts another function. This is

especially important for callbacks, event handlers, and higher-order

functions.

from collections.abc import Callable

def apply(values: list[int], fn: Callable[[int], int]) -> list[int]:

return [fn(v) for v in values]If the signature is unknown in advance, you can use

Callable[..., ReturnType], but this should be a last resort.

## Generics

Generics are parameterized types. In simple terms, these are types that

accept other types. This matters when you want to preserve the relation

between input and output instead of losing it to Any. For example,

first returns the same item type as inside the input collection:

from collections.abc import Sequence

from typing import TypeVar

T = TypeVar("T")

def first(items: Sequence[T]) -> T:

return items[0]Without generics, you would write Sequence[Any] and lose output type.

With generics, the analyzer knows that if input is Sequence[str], the

result is str. This is especially important for collections, factories,

and repositories where one implementation handles multiple types.

It is also useful to know that TypeVar has a bound parameter that

restricts which types can be used in a generic:

from collections.abc import Hashable, Iterable

from typing import TypeVar

HashableT = TypeVar("HashableT", bound=Hashable)

def mode(data: Iterable[HashableT]) -> HashableT:

...## Literal

Literal lets you fix exact allowed values, not just a base type. This

is useful when a parameter has a closed set of modes, statuses, or keys.

from typing import Literal

def export_report(format: Literal["csv", "json"]) -> bytes:

...The signature above defines the contract clearly: no third format

exists here. This makes APIs clearer and lets type checkers catch typos

such as "jsno" before runtime.

## Static Analyzers

Now it is time to discuss what makes typing practical in Python: static analyzers. They read annotations, compare them with actual code, and report problems before runtime.

mypyis the classic static type checker for gradual typing. Strength: plugin ecosystem and precise per-module strictness tuning. Weakness: without tuning it can be either too soft or too noisy.pyrightis a fast and clear checker. Strength: good diagnostics and fast feedback. Weakness: plugin-style extensibility is weaker than inmypy.pyreflyis a new fast Rust analyzer. Strength: high speed and LSP integration. Weakness: still young, so some behavior may change.tyis a new Rust tool by Astral (currently beta). Strength: speed and modern architecture. Weakness: pre-release stage; feature set is still catching up to mature checkers.

You can install and run them with uv:

uv tool install mypy

uv tool install pyright

uv tool install pyrefly

uv tool install tyuvx mypy .

uvx pyright .

uvx pyrefly check

uvx ty checkHere is a business-oriented example with intentional typing mistakes:

from dataclasses import dataclass

from typing import NewType

UserId = NewType("UserId", int)

@dataclass

class User:

id: UserId

email: str

is_active: bool

def discount(total: int, percent: int) -> int:

return total - total * (percent / 100)

def send_invoice(user: User, amount: int) -> str:

if not user.is_active:

return None

return f"invoice for {user.email}: {amount}"

def main() -> None:

user = User(id=42, email=123, is_active="yes")

total = discount("1000", 10)

send_invoice(user, "500")Running pyright on this file will produce messages roughly like:

error: Type "float" is not assignable to return type "int"

error: Type "None" is not assignable to return type "str"

error: "Literal[42]" is not assignable to "UserId"

error: "Literal[123]" is not assignable to "str"

error: "Literal['yes']" is not assignable to "bool"

error: "Literal['1000']" is not assignable to "int"

error: "Literal['500']" is not assignable to "int"What matters in this output:

- Errors in

discountandsend_invoiceshow function contract violations: the signature promises one thing, implementation does another. - Errors in

mainshow boundary-layer issues (input/DTO) passing wrong types into domain logic. - The

UserIderror demonstrates whyNewTypeis useful in business code: a user identifier cannot be accidentally replaced by a plainintwithout an explicit decision.

## Stub Files (.pyi)

Sometimes you want typing for code you cannot or should not edit.

Examples: generated code, third-party library code, or your own module

where you do not want to mix typing and implementation. That is what

stub files with .pyi extension are for.

A .pyi file contains type signatures only and no implementation.

Static analyzers look for these files near source code or in dedicated

types-* packages. Example:

calc.py:

def add(a, b):

return a + bcalc.pyi:

def add(a: int, b: int) -> int: ...This way you can keep typing separate from implementation, sometimes even without access to source code.

## TypeAlias

When a type gets complex, move it into an alias to keep signatures

readable. This is especially useful for business terms like UserId,

Currency, or Payload.

from typing import TypeAlias

UserId: TypeAlias = int

Payload: TypeAlias = dict[str, str | int | float]Then you can write:

def send(user_id: UserId, payload: Payload) -> None:

...In Python 3.12+, you can use the type statement instead:

type UserId = int

type Payload = dict[str, str | int | float]This is the same alias, just shorter and easier to read.

## TypeAlias vs NewType

TypeAlias is just a type synonym, it does not create a new type.

NewType creates a distinct type at static-checking level, even though

at runtime it is just a wrapper function. This is useful when you have

logically different values of the same base type, for example UserId

and OrderId.

from typing import NewType, TypeAlias

UserId: TypeAlias = int

OrderId = NewType("OrderId", int)

def get_user(user_id: UserId) -> None:

...

def get_order(order_id: OrderId) -> None:

...UserId and int are treated as the same type. OrderId is not

compatible with int without explicit conversion.

# How to Use Typing Correctly

Set the right expectation first. Like tests, the purpose of types is to fail when the code is wrong. If they never fail, they are not doing useful work. The less forgiving your typing setup is, the better it protects your code. Strict typing (like strict tests) catches bugs, but only if checks can actually fail.

Writing truly correct typed code is hard. It is a separate skill that grows the same way architecture and testing skills grow. So start small and increase strictness gradually.

##

Returning None

Also consider the case where a function returns nothing:

def print_weather(weather: Weather):

print("Weather:")

for date, data in weather.by_days().items():

print(date)

print(f"\t{data.temperature}")

print(f"\t{data.humidity}")

print(f"\t{data.wind_speed}")

print("========")

tmp = print_weather(Weather()) + 1In Python, if a function has no return, it returns None. Static

analyzers know this too. For example, pyright on this intentionally

broken code will show:

error:

Operator "+" not supported for types "None" and "Literal[1]"This shows that pyright understands the return type as None. Does

that mean you can skip return annotations? No. First,

PEP 20 says explicit is better

than implicit. Second, consider developer experience (DX) in Python. Everyone

knows typing is optional, so missing return annotation is ambiguous.

When you see a function signature without return type, you cannot tell

whether the author skipped typing or the function really returns None.

You resolve that only by reading implementation details, which slows

code navigation.

## Function Input vs Output

Continuing the return-type topic: avoid using abstract classes from

collections.abc, or custom abstract classes, for function return

types. They are better suited for input types where you want broad

polymorphism. Return values should be concrete so it is clear how to

use the result.

ImportantA function should be more explicit about what concrete type it returns than what it accepts.

If you want to go deeper, here are useful resources to configure your tools and understand Python typing in detail: